Today, we’ll train a quadruped to walk in a virtual environment.

Or, to put it better: we’ll train a quadruped to move forward as fast as possible without falling. It’s free to choose any strategy: walking, crawling, rolling, or even flying (if the simulation allows it). I want to turn this into a personal challenge: to learn the fundamentals of this topic, code it, train it, and see it in action in one day.

To achieve this, we must simulate the laws of physics. In other words, the virtual world must behave like the real world. There should be gravity, forces, collisions, just like in a game engine. If you look for simulations for robotics you will mostly see Gazebo, MujoCo and Isaac Gym. To keep this blog simple we’ll use a lightweight physics engine called pybullet.

Okay, the physics engine is ready. But how do we get a robotic dog? In robotics simulations, robots are described by URDF (Unified Robot Description Format) files, which define the robot’s shape, joints, mass, and how all parts are connected.

One robotic dog model that many researchers and hobbyists use is called AlienGo (by Unitree Robotics). By simply loading the aliengo.urdf file into our PyBullet environment, we can instantly spawn a fully articulated virtual quadruped with legs, joints, motors, and physics properties.

Let’s code

In the following code, we define a Python class called QuadrupedEnv that sets up a complete PyBullet simulation environment

import pybullet as p

import pybullet_data

import time

class QuadrupedEnv():

def __init__(self):

super(QuadrupedEnv, self).__init__()

# If you are not using Mac, I read that you can disable debug windows with options:

# self.physics_client = p.connect(p.GUI, options="--disable-analytics --disable-rendering-preview")

# Connect, then disable debug windows manually

self.physics_client = p.connect(p.GUI)

p.configureDebugVisualizer(p.COV_ENABLE_GUI, 0) # Hides right control panel

p.configureDebugVisualizer(p.COV_ENABLE_SEGMENTATION_MARK_PREVIEW, 0)

p.configureDebugVisualizer(p.COV_ENABLE_DEPTH_BUFFER_PREVIEW, 0)

p.configureDebugVisualizer(p.COV_ENABLE_RGB_BUFFER_PREVIEW, 0)

p.setGravity(0, 0, -9.8)

self.time_step = 1 / 240

p.setTimeStep(self.time_step)

# Load the robot and ground

p.setAdditionalSearchPath(pybullet_data.getDataPath()) # Add PyBullet's default data folder

start_pos = [0, 0, 0.5]

self.plane_id = p.loadURDF("plane.urdf")

self.robot_id = p.loadURDF("aliengo/aliengo.urdf", start_pos)

for i in range(10000):

p.stepSimulation()

time.sleep(self.time_step)

env = QuadrupedEnv()

env.close()

Some interesting things about the code:

- We set the gravity to -9.8, because realistics Earth gravity is -9.8 m/s²

- We set the time step as 1/240. This means the physics engine updates 240 times per second.

- setAdditionalSearchPath tells PyBullet where to look for built-in models like plane.urdf or aliengo.urdf. Without this, we would need to provide the full path to every asset.

- The loop runs the simulation for 10,000 steps, if each step is 1/240 of a second, then the whole simulation runs in front of our eyes for 10000/240 = 41.6 seconds.

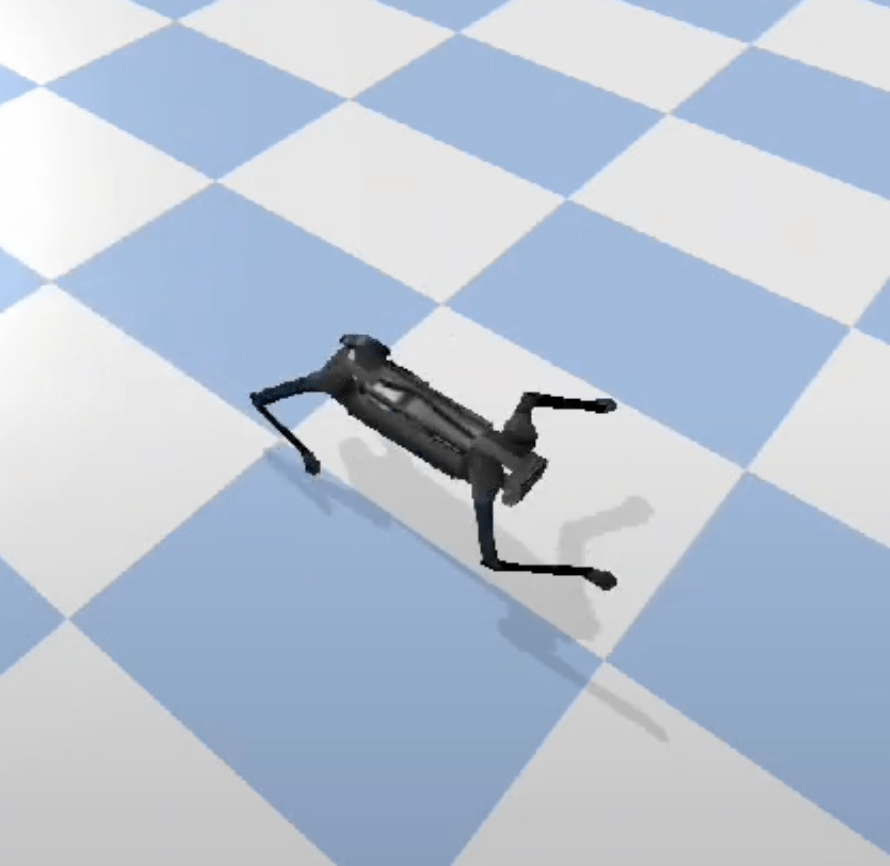

Now we have a dog:

Setting a proper environment

It’s nice to see Aliengo in a simulation, but it doesn’t do much. It patiently waits for his simulation steps to end while I drag it around.

I want the robot to learn to move forward, and I’ll use reinforcement learning for this task. In reinforcement learning, the robot doesn’t have a fixed set of instructions, it learns a policy.

A policy is simply a strategy: it takes in what the robot senses about the world (its “observation”) and decides what action to take next (how to move its joints). At first, the policy will be random and clumsy, but as we train it through rewards and feedback, the policy will get better at choosing movements that help the robot walk forward without falling.

In my code an episode ends under either of two conditions:

- The robot falls. If it falls over, there’s no sense in having it struggle to stand back up. We are not interested in this task for now ( also it’s painful to watch 😓); we simply reset and start a new episode.

- 1,000 simulation steps have elapsed. This is a time-limit so I can focus on the transition from standing to walking and keep episodes short.

We will inherit OpenAI’s gym Environment and add the following:

- action space:

The robot should move 3 motors on each leg. The values are between -1 and 1 because actions are normalized:

self.action_space = spaces.Box(low=-1, high=1, shape=(12,), dtype=np.float32)

- observation space:

Normally Aliengo has a camera, but in this simple experiment we are trying to see if we can create a walking robot just by observing its own position, orientation and speed.

obs = (

base_pos 3 values (x,y,z)

+ base_orn 4 values (x, y, z, w)

+ base_vel 3 values

+ base_ang_vel 3 values

+ joint_positions 12 values (3 motors per leg)

+ joint_velocities 12 values

)

self.observation_space = spaces.Box(

low=-np.inf, high=np.inf, shape=(37,), dtype=np.float32

)

- step(action):

Every time our agent takes an action, we return the observation, reward and done.

observation: In our case, observation is just the orientation and speed of the robot (in full code you can check out my get_observation function)

reward: We will come back to this later, it’s the most important part of reinforcement learning!

done: this is a boolean value and as i mentioned above it terminates the episode if robot falls or 1000 steps have elapsed.

Reward and punishment

I mentioned that each step calculates a reward, but what exactly is a reward? In reinforcement learning, designing a good reward function is actually a major research area, often referred to as reward design or reward shaping. For now, I tried to formulate a reward based on common knowledge, but I would love to explore this field more deeply in the future.

Let’s start with a simple reward: I just want this dog to move forward. so it gets a point every time it moves forward:

forward_progress = (base_pos[0] – self.previous_x_position) * 50

But while doing that, I don’t want it to fall:

# Check if the robot is tilted beyond the threshold

if abs(roll) > tilt_threshold or abs(pitch) > tilt_threshold:

fall_penalty = -10

How did I come up with these coefficients? Well, when I used a smaller fall_penalty, the robot would throw itself forward and call it a day. When I set a high fall penalty (like -50), it became too scared to move and would just vibrate its way forward. So these values really come from trial and error—there’s no deeper logic behind them.

It was going fine, but sometimes it would drift to the left or right, so I penalized its rotation.

Yes, it would probably have converged to a normal walking behavior without this change, but I wanted results in the minimum number of episodes:

yaw_penalty = -abs(yaw) * 0.01

I also realized that even though it moved forward with this formula, it would move its legs like it was having a nervous breakdown. So, I added an energy penalty to discourage excessive movements:

# Calculate servo movement penalty (sum of absolute differences)

energy_penalty = -0.01 * np.sum(

np.abs(current_joint_positions – self.previous_joint_positions)

)

Our final reward formula looks like this:

reward = forward_progress + fall_penalty + yaw_penalty + energy_penalty

To keep the details out of this post, here’s the final environment. Keep in mind that this code was written in a rush—use with caution. 🙂

import gym

from gym import spaces

import pybullet as p

import pybullet_data

import numpy as np

import math

from torch.utils.tensorboard import SummaryWriter

class QuadrupedEnv(gym.Env):

def __init__(self, experiment_name):

super(QuadrupedEnv, self).__init__()

experiment_path = "runs/" + experiment_name

self.writer = SummaryWriter(experiment_path)

# Define action space: 12 controllable joints (normalized to [-1, 1])

self.action_space = spaces.Box(low=-1, high=1, shape=(12,), dtype=np.float32)

self.step_count = 0

self.step_count_cumulative = 0

# Define observation space: 37 elements (base state + joint positions/velocities)

self.observation_space = spaces.Box(

low=-np.inf, high=np.inf, shape=(37,), dtype=np.float32

)

# PyBullet setup

self.physics_client = p.connect(p.DIRECT) # Use DIRECT for high FPS

p.setAdditionalSearchPath(pybullet_data.getDataPath())

p.setGravity(0, 0, -9.8)

# Load the robot and ground

self.plane_id = p.loadURDF("plane.urdf")

self.robot_id = p.loadURDF("aliengo/aliengo.urdf", [0, 0, 0.5], p.getQuaternionFromEuler([0, 0, 0]))

# Define joint indices for the 12 controllable joints

self.controllable_joints = [

1, 2, 3, # Front-right leg

5, 6, 7, # Front-left leg

9, 10, 11, # Rear-right leg

13, 14, 15 # Rear-left leg

]

# i changed some limits for demonstration

self.joint_limits = {

1: [-1.2217304764, 1.2217304764], # FR_hip_joint

2: [-1.0, 1.0], # FR_upper_joint

3: [-2.77507351067, -0.645771823238], # FR_lower_joint

5: [-1.2217304764, 1.2217304764], # FL_hip_joint

6: [-1.0, 1.0], # FL_upper_joint

7: [-2.77507351067, -0.645771823238], # FL_lower_joint

9: [-1.2217304764, 1.2217304764], # RR_hip_joint

10: [-1.0, 1.0], # RR_upper_joint

11: [-2.77507351067, -0.645771823238], # RR_lower_joint

13: [-1.2217304764, 1.2217304764], # RL_hip_joint

14: [-1.0, 1.0], # RL_upper_joint

15: [-2.77507351067, -0.645771823238], # RL_lower_joint

}

# Initialize previous joint positions

self.previous_joint_positions = np.zeros(len(self.controllable_joints))

self.set_initial_state()

# Simulation timestep

self.time_step = 1 / 240

p.setTimeStep(self.time_step)

# Previous x position for reward calculation

self.previous_x_position = 0.0

def seed(self, seed=None):

self.np_random, seed = gym.utils.seeding.np_random(seed)

p.setPhysicsEngineParameter(fixedSeed=seed)

return [seed]

def step(self, action):

# Define the maximum allowable movement per step based on servo speed

# todo: experiment with different values

max_step_size = 0.5

for i, joint_index in enumerate(self.controllable_joints):

# Get joint limits

joint_min, joint_max = self.joint_limits[joint_index]

# Map normalized action [-1, 1] to joint limits

target_position = np.interp(action[i], [-1, 1], [joint_min, joint_max])

# Get the current joint position

current_position = p.getJointState(self.robot_id, joint_index)[0]

# Calculate the movement toward the target while respecting the speed constraint

movement = np.clip(target_position - current_position, -max_step_size, max_step_size)

# Update the joint's new position

new_position = current_position + movement

# Apply the new position

p.setJointMotorControl2(

self.robot_id,

joint_index,

p.POSITION_CONTROL,

targetPosition=new_position,

force=44.4,

)

# Step simulation

p.stepSimulation()

#time.sleep(self.time_step)

# Get observations

obs = self._get_observation()

# Calculate reward

reward = self._compute_reward()

# Check termination conditions

self.step_count += 1

self.step_count_cumulative += 1

if self.step_count >= 1000:

done = True

else:

done = self._check_done()

return obs, reward, done, {}

def set_initial_state(self):

# Desired joint angles in radians for initial position

hip_angle = 0 # 45 degrees

upper_leg_angle = np.pi / 4 # -45 degrees

lower_leg_angle = -np.pi / 2 # -90 degrees

# Assign joint angles to corresponding joints

for i, joint_index in enumerate(self.controllable_joints):

if i % 3 == 0: # Hip joints

target_angle = hip_angle

if i % 3 == 1: # Upper leg joints

target_angle = upper_leg_angle

elif i % 3 == 2: # Lower leg joints

target_angle = lower_leg_angle

# Set the joint to the desired position

p.resetJointState(self.robot_id, joint_index, target_angle)

p.resetBasePositionAndOrientation(

self.robot_id,

[0, 0, 0.4], # [x, y, z] position

[0, 0, 0, 1], # Neutral orientation as quaternion [x, y, z, w]

)

def reset(self):

p.resetSimulation()

p.setGravity(0, 0, -9.8)

self.plane_id = p.loadURDF("plane.urdf")

self.robot_id = p.loadURDF(

"aliengo/aliengo.urdf", [0, 0, 0.5], p.getQuaternionFromEuler([0, 0, 0])

)

self.set_initial_state()

# Initialize the previous x position

self.previous_x_position = 0.0

# for resetting the env if more than 1000 frames pass.

self.step_count = 0

# Return initial observation

return self._get_observation()

def _compute_reward(self):

# Get current joint positions

joint_states = p.getJointStates(self.robot_id, self.controllable_joints)

current_joint_positions = np.array([state[0] for state in joint_states])

# Calculate servo movement penalty (sum of absolute differences)

energy_penalty = -0.01 * np.sum(

np.abs(current_joint_positions - self.previous_joint_positions)

)

# Update previous joint positions for the next step

self.previous_joint_positions = current_joint_positions

# Get the robot's base position and orientation

base_pos, base_orn = p.getBasePositionAndOrientation(self.robot_id)

# Convert quaternion to Euler angles

base_euler = p.getEulerFromQuaternion(base_orn)

roll, pitch, yaw = base_euler # Extract roll, pitch, and yaw

# Set tilt threshold in radians (e.g., 45 degrees = π/4 radians)

tilt_threshold = math.pi / 4 # 45 degrees

# Check if the robot is tilted beyond the threshold

if abs(roll) > tilt_threshold or abs(pitch) > tilt_threshold:

fall_penalty = -10 # Assign fall penalty

else:

fall_penalty = 0 # No penalty if within limits

# Calculate forward movement (difference in x-position)

forward_progress = (base_pos[0] - self.previous_x_position) * 50

# Penalize yaw deviation (discourage rotation)

yaw_penalty = -abs(yaw) * 0.01

# Update the previous x position for the next step

self.previous_x_position = base_pos[0]

# Combine forward progress, fall penalty, yaw penalty, and energy penalty

reward = forward_progress + fall_penalty + yaw_penalty + energy_penalty

# Log metrics to TensorBoard

self.writer.add_scalar(

"rollout/forward_reward", forward_progress, self.step_count_cumulative

)

self.writer.add_scalar(

"rollout/yaw_penalty", yaw_penalty, self.step_count_cumulative

)

self.writer.add_scalar(

"rollout/movement_penalty", energy_penalty, self.step_count_cumulative

)

self.writer.add_scalar(

"rollout/total_reward", reward, self.step_count_cumulative

)

return reward

def _check_done(self):

# Get the robot's base position and orientation

base_pos, base_orn = p.getBasePositionAndOrientation(self.robot_id)

# Convert quaternion to Euler angles

base_euler = p.getEulerFromQuaternion(base_orn)

roll, pitch, _ = base_euler # Extract roll and pitch

# Set tilt threshold in radians (e.g., 45 degrees = π/4 radians)

tilt_threshold = math.pi / 2 # 90 degrees

# Check if the robot is too tilted or fell too low

if (

abs(roll) > tilt_threshold

or abs(pitch) > tilt_threshold

or base_pos[2] < 0.05

):

print(

f"Robot fell! Roll: {roll:.2f}, Pitch: {pitch:.2f}, Height: {base_pos[2]:.2f}"

)

return True # End the episode

return False

def _get_observation(self):

# Get robot's state

base_pos, base_orn = p.getBasePositionAndOrientation(self.robot_id)

base_vel, base_ang_vel = p.getBaseVelocity(self.robot_id)

joint_states = p.getJointStates(self.robot_id, self.controllable_joints)

joint_positions = [state[0] for state in joint_states]

joint_velocities = [state[1] for state in joint_states]

# Flatten observation

obs = (

list(base_pos)

+ list(base_orn)

+ list(base_vel)

+ list(base_ang_vel)

+ joint_positions

+ joint_velocities

)

return np.array(obs, dtype=np.float32)

Training

In 2017, OpenAI released Baselines. It was a collection of popular reinforcement learning algorithms in TensorFlow. Since it was open source, people used it and created a better version called Stable Baselines. Later, a PyTorch version, Stable Baselines3, was released.

We will import PPO from stable_baselines3 and and train our model:

import os

from stable_baselines3 import PPO

from stable_baselines3.common.vec_env import SubprocVecEnv

from stable_baselines3.common.callbacks import CheckpointCallback

from environment import QuadrupedEnv

num_envs = 4

experiment_name = "experiment_10m"

# Fix for MacOS multiprocessing (spawn method)

if __name__ == "__main__":

os.environ["PYTHONWARNINGS"] = "ignore::UserWarning"

# Function to initialize the environment

def make_env(experiment_name):

def _init():

return QuadrupedEnv(experiment_name=experiment_name)

return _init

env = SubprocVecEnv([make_env(experiment_name) for _ in range(num_envs)])

# PPO Model Setup

model = PPO(

"MlpPolicy",

env,

learning_rate=0.0003,

verbose=1,

tensorboard_log="./ppo_quadruped/",

)

# Checkpoint callback

checkpoint_callback = CheckpointCallback(

save_freq= 100_000 // num_envs,

save_path=f"./model_checkpoints/{experiment_name}/",

name_prefix=experiment_name,

)

# Train the model

model.learn(total_timesteps=10_000_000, callback=checkpoint_callback)

# Save the model

model.save(experiment_name)

# Close the environments

env.close()

Cool! There’s nothing too fancy here:

- SubprocVecEnv launches four instances of our QuadrupedEnv in parallel, so we step all four at once and collect experience much faster. (Speaking of speed, you might have noticed that in environment.py we launch PyBullet in DIRECT mode and omit any time.sleep() calls—this headless setup removes rendering overhead so our simulation steps at full speed)

- PPO (“Proximal Policy Optimization”) learns a policy to make our quadruped walk.

- TensorBoard logs training curves (loss, reward, etc.) under ./ppo_quadruped/.

- CheckpointCallback snapshots our model every 100k timesteps so we can see intermediate behaviors.

What is PPO?

I first heard about it when OpenAI released that insane video of the hide-and-seek agents. As a computer science student back then, when I thought about powerful algorithms, I usually imagined ones that were invented about 50 years ago. But some algorithms are actually very new—and their creators are still actively working in the field today. PPO is one of them.

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) was introduced by OpenAI in 2017. It’s called “proximal” because every update is forced to stay close (proximal) to the old policy. It was mainly developed by researcher John Schulman, who also contributed to earlier algorithms like TRPO (Trust Region Policy Optimization).

Policy-gradient: PPO tweaks the robot’s policy directly, instead of first building a giant table of Q-values.

Stochastic policy: Early on, the robot picks actions with some randomness so it can explore.

Advantage estimate: After each action, we measure “Was that better than we expected?” This score is the “advantage”.

Clipped surrogate objective: We try to push the policy toward better actions, but we clip the push if it gets too strong. This creates a mini trust region that stops wild swings.

On-policy: Because those clips rely on fresh data, we gather new experience every training round, use it once, then throw it away.

Entropy bonus: We add a small reward for keeping decisions a bit random, delaying premature convergence on a single strategy.

PPO has quite a few hyper-parameters you can tune. Because it’s fairly robust, you can experiment with different values without the training blowing up. Since my goal was to build a quick proof-of-concept in one day, I just kept the defaults.

Here’s the result with the this simple experiment:

As you can see, it learned a “gecko” gait instead of a cheetah-like one. So why on earth is this happening?

I think the short episode length encouraged a greedy strategy. As you might recall, I defined an episode to end either when the robot falls or after 1000 simulation steps. That’s a very short time for discovering a dynamic and efficient gait.

I mean, if you think about it, even if you’re a cheetah, you need time to build up momentum then accelerate. In contrast, a gecko can move almost immediately using short, stable steps and a low center of mass. So, the agent learns to hug the ground and inch forward like a gecko, maximizing its short-term reward while avoiding falls.

Or maybe I’m just overanalyzing a bad policy that converged to a local optimum.

What’s next?

There are lots of interesting questions now. How do we evaluate the policy? What happens if we generate different obstacles each time? Should we introduce random delays in the motors to help shrink the sim-to-real gap? And seriously, why is my robot walking so weird? I think these problems deserve their own blog post. For now, I’ve completed my challenge of teaching a quadruped to walk in just one day.

This field is incredible, but I can’t help feeling like I’m late to the party. Then again, you know what they say: the best time to learn reinforcement learning was 10 years ago… the second-best time is today.

Yorum bırakın