You can program a robot arm to do almost anything. At the end of the day, you’re just setting servo angles, and the computer executes them like any other program.

def grab_coffee_cup(): # Move shoulder to 45 degrees, elbow to 90 degrees servo_shoulder.set_angle(45) servo_elbow.set_angle(90) gripper.close()But there’s a problem.

The problem

If the coffee cup is moved just 1cm to the left, the servo angles will send the gripper to the old location. The robot will likely knock the cup over because it has no way of knowing the world has changed. Clearly we need some kind of intelligence here.

Computer vision

A common suggestion is to add computer vision. Detect edges, detect objects, and you’re done.

Still, edge and object detection help you see the world but they don’t teach the robot what to do in it. So instead of using computer vision and manually programming movements of a robot, we need to predict the robot’s actions.

Transformers

What if we used transformers here too? We saw that they work in language, vision and even audio models. Why can’t we use them for robotics too? In this blog post, we will explore what a transformer architecture can actually give us in robotics, specifically through a method called ACT.

ACT

Instead of predicting a single action at every timestep, ACT predicts chunks of actions at once. By predicting k actions at once, the model makes decisions k times less often, which directly limits how much small errors can accumulate and push the robot off its training distribution.

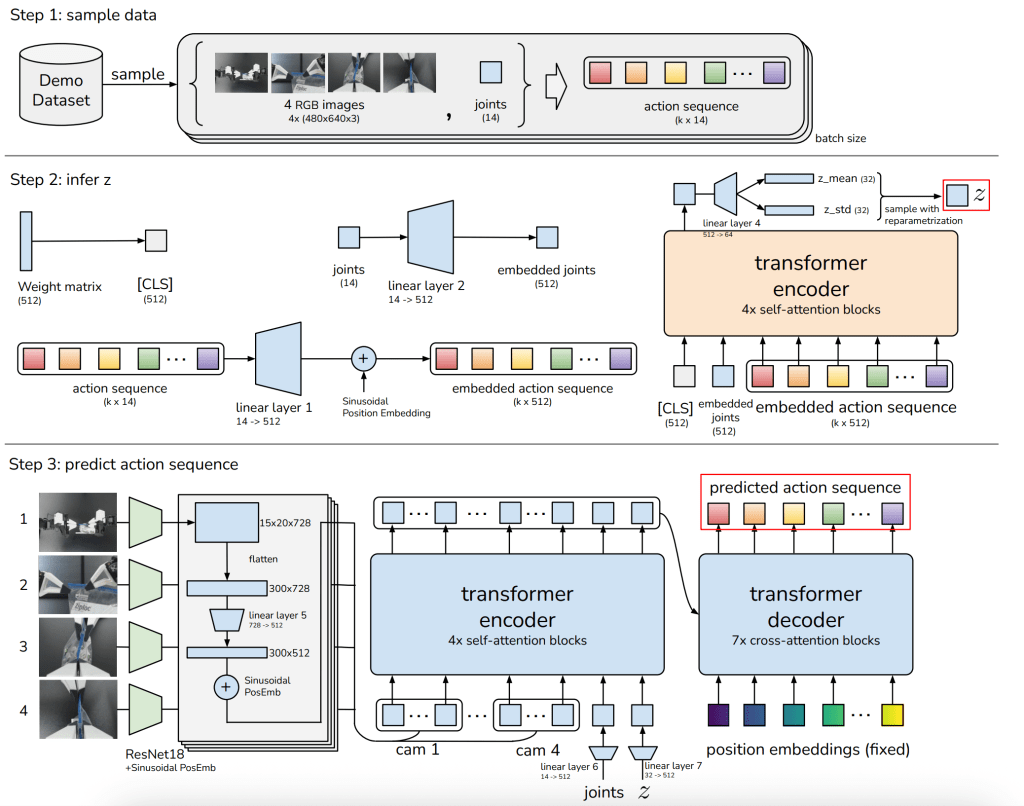

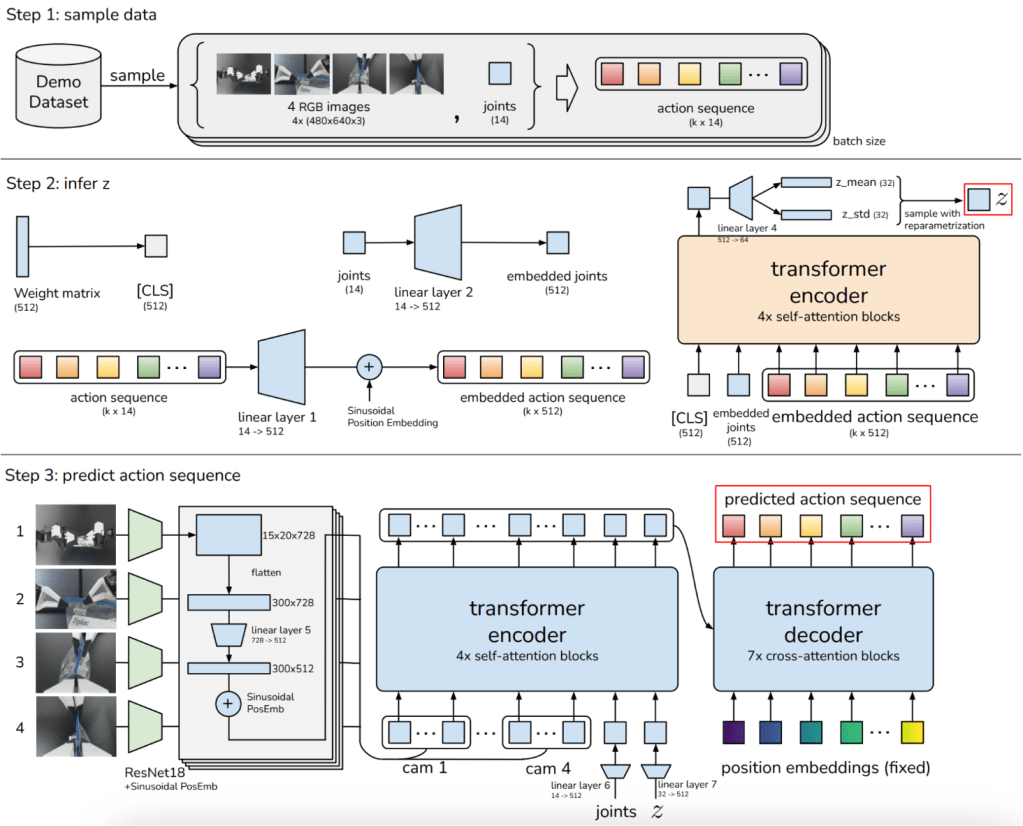

If you look at the ACT paper Learning Fine-Grained Bimanual Manipulation with Low-Cost Hardware , they introduce a number of interesting ideas—from the open-source hardware system they designed to the temporal ensembling of predictions. But I want to focus on the end of the paper, where they present a clear architecture diagram. By the end of this blog post, you’ll understand every detail of the following architecture:

the X and the y

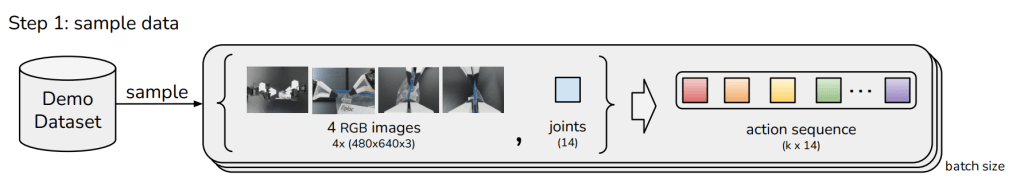

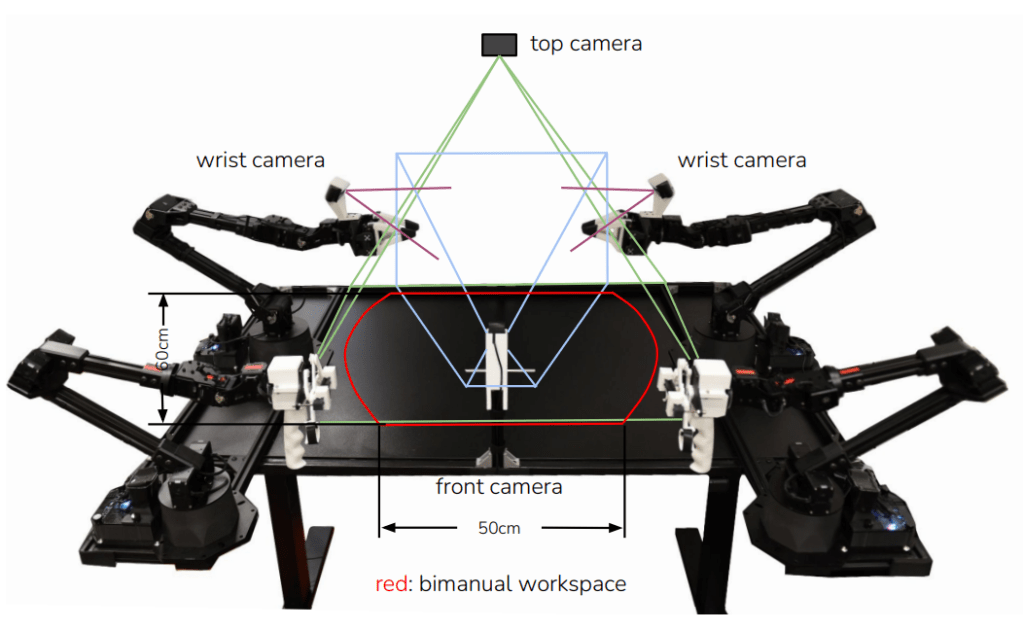

The dataset consists of video footage and the joint positions of sequence of actions. The data is collected through teleoperation with the ALOHA:

In this setup, a human operator controls two Leader arms in the front, which are identical in scale and kinematic structure to the two Follower arms positioned behind them. As the operator moves the leader arms, the follower arms mimic those movements in real-time to perform tasks like picking up a coffee cup or threading a needle. While the human demonstrates the task, the system simultaneously records the visual state from multiple cameras and the precise 14-joint positions.

As input we give the model 4 RGB images (current state of the top, front and two wrist cameras) and the 14 joint positions (7 joints per arm) and the model predicts the next k positions of these arms.

Why not a classic deep learning approach?

Now that we have the X and y batches, I can’t help but think about using a simple neural network architecture. But there is a problem with the sequential data that we have.

Most standard deep learning architectures are trained with Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss function as deterministic regressors. They attempt to learn a function that minimizes the Euclidean distance to the ground truth. This works well when there is a single, well-defined correct answer. For example, predicting the house price, estimating depth from stereo images, or forecasting temperature given historical measurements all have relatively clear ground truth targets.

In robotics, however, there is often no single correct answer.

Multimodality in robotics

Multimodality means that multiple valid actions can solve the same task. So (state → action) is not a one-to-one problem; it is one-to-many. I can grasp a cup from the left or from the right, move fast or move slowly, take a wide arc or a straight path. When trained with MSE, a deterministic model will try to average these possibilities.

For example, let’s say that in the data, half of the demonstrations grasp the cup using the left arm, and the other half use the right arm. A deterministic model trained with MSE has no way to represent these two distinct strategies. Instead, it will minimize error by predicting the average of the two behaviors. As a result, whenever the model sees a cup, it may move both hands slightly toward the cup, stop halfway, and call it a day. 😵

the cVAE

The second part of the diagram shows how to infer the z. To understand it, we need to understand conditional variational auto encoders (cVAE). To do that lets go from E to AE to VAE to finally cVAE’s.

E

An encoder is a neural network that compresses high-dimensional input (like a picture or a sentence) into a compact latent representation.

How can data be represented in latent space? Before understanding how computers can do it, let’s do an experiment on ourselves. Take a look at this image:

What you are seeing is about a million pixels. But our minds can encode it with words. For example I can encode this image like:

[red circle, green square, blue x, blue x, green x, … pink circle]

Now instead of 1048576 pixels we have a small text. This small text doesn’t mean anything useful to someone else, only you and I know that it represents the type of image I showed you. Latent space is similar to this example. Instead of text, we have vectors, lists of numbers that act as coordinates in a multi-dimensional map.

AE (Autoencoder)

The decoder does the opposite of the encoder. It takes that compact latent representation and reconstructs the original input. When you connect an encoder and a decoder, you can compress things and then uncompress them; this is called an Autoencoder. It is useful for compression, denoising (feeding it a grainy image and forcing it to reconstruct a clean one) or anomaly detection (if the autoencoder can’t reconstruct an image, that image must be defective)

For our example, decoding is taking the latent instructions (red circle, green circle…) and trying to draw the image.

But if you want to generate something new, you cannot use a standard autoencoder because the latent space is “messy”. If you pick a random point in that space that the model hasn’t seen before, the decoder will likely produce garbage/noise.

VAE (Variational Autoencoders)

That’s where the Variational Autoencoder comes into place. It forces the latent space to follow a smooth shape (a Gaussian distribution). Because the space is now smooth and predictable, you can pick a random point and get a valid, realistic output. These structures are used in generative art, drug discovery etc.

So now instead of only producing the latent representation, the encoder predicts the mean and variance of this latent space. We can sample any point within that distribution (effectively ‘trying out’ random variations) and the decoder will still be able to reconstruct a valid, realistic output.

cVAE

But what if you want to control the output based on an input? Right now, there is no input to the decoder other than a random vector. And that’s the last letter for us: the Conditional part. We are introduced with a “Condition” (label or context) that is fed into both the encoder and the decoder. So now, instead of just “Generate an action” we can say: “Generate an action, given that this images and joint positions”

Now that we have a general understanding of the cVAE’s, let’s take a look at the ACT’s encoder.

as an input we give:

- the [CLS] token. If you’re familiar with BERT, you know this one. It’s a special, learned token whose only job is to aggregate information. Think of it as a sponge that’s going to soak up the context from the rest of the sequence.

- current joint positions

- target action sequence

Now you may wonder how joint positions and actions dimensions expanded from 14 to 512?

To get from 14 to 512, the raw values are passed through a linear projection layer—essentially a matrix multiplication with learnable weights, that mathematically expands the input vector. This embedding process translates the literal joint coordinates into a rich, high-dimensional feature representation that matches the size of the [CLS] token and other inputs. With this standardization all data types share the same dimension (512), allowing the Transformer to mix and process them together using its attention mechanism. Inside the Transformer, self-attention allows that [CLS] token to ‘look at’ the joints and the future actions, effectively summarizing the motion.

Now, the Transformer outputs a vector for every single item in the sequence. But we discard almost all of it. We ignore the outputs for the joints. We ignore the outputs for the action sequence. We only keep the output corresponding to that [CLS] token. Because that single token has effectively summarized the entire style of the demonstration. We take that one vector, project it down to get a Mean and a Variance to sample our style variable, z.

The style variable z

So, what is z? As you can see, the input does not include camera footage; we only have the current joint positions and the action sequence. Therefore, if we are sampling from a summary of this data, it must be purely about the movement itself. This raises the question: What is the “style” of the movement? It can be something like:

- Is the arm moving left slowly?

- Is it quickly grabbing an object?

- Is it lifting something high with the grippers closed?

Even though the encoder has no visual footage, it can still infer that there are distinct “modes” or patterns in the action sequences. By introducing this variable z, we have taken a significant step toward solving the multimodality problem I mentioned earlier.

The decoder

Don’t let the word “Encoder” confuse you here. We aren’t talking about the previous step that created the style variable (z). We are now entering the main brain of the robot: the Policy Transformer.

This Transformer has an Encoder that takes in three things:

- The Style (z)

- Current joint positions

- The Eyes: Footage from 4 cameras. For the first time we are including the visual data to the architecture.

It mixes these ingredients together to produce a rich, contextualized Memory. Think of this Memory as a complete understanding of the current moment: “I see a cup to my right, my arms are currently low, and I need to slowly move my left arm toward the cup (z).”

To get actual movement, we need the Decoder. The Decoder works by asking questions using a set of fixed Action Queries.Think of these queries as empty slots waiting to be filled. Query 1 asks the Memory: “Given the style and the cup location, what is my FIRST move?” Query 2 asks: “What is my SECOND move?” (and so on). The Decoder takes these empty questions, looks at the Memory (Keys and Values), and fills in the blanks. The answers it writes down become the Action Chunk, the precise trajectory the robot will now execute.

Something doesn’t add up

“But did you notice something? This z here is the style of the target action sequence. But at test time, we don’t know the target. That’s the whole point—we are trying to predict it!

This is why the Encoder is strictly a training tool. We don’t use the encoder or the z variable during testing. But if we are going to throw away z, then why did we bother with it?

By forcing the Decoder to use z during training, we taught it that ‘Going Left’ and ‘Going Right’ are two completely different ‘modes’ or styles. We forced it to organize its policy into distinct strategies. It now understands that these are separate options, not to be mixed.

Replacing z during inference

So, at inference time, we simply feed it a zero. Zero is the mean of the distribution. It basically means: ‘I have no specific preference today, so just give me the most standard, average behavior you know.’ And that might be using the left arm to grasp or moving the right arm forward. We still don’t have any control over the style, but at least the model knows that “styles of movement” exist.

A specialist cannot compete in this age

ACT is incredibly impressive but it suffers from a “one-track mind.” One policy equals one task. If you want a robot to fold laundry, make coffee, and open a door, you effectively need three different ACT models.

In the world of LLMs, we already learned this lesson. We don’t have a “Poet-Bot,” a “History-Bot,” or a “Friendly-Bot” sitting on different servers. We have a single, massive model that saw diverse data during training and, as a result, became a Generalist. We discovered that generalists don’t just match specialists, they often outperform them because knowledge of “how to write a poem” actually helps the model understand the nuances of “how to write a historical essay.”

Next steps in robotics

ACT is from 2024, and while it was a foundational step in learning how to handle robot “style” and “chunks,” the field has rapidly moved toward. In my next blog posts, I would like to talk about VLA’s and how we are finally giving robots a “common sense” understanding of the physical world.

Yorum bırakın